Editor’s Note:

In the original print version of this article, there was an error stating that Michael’s sobriety date was December 14 after he stopped drinking, but that he continued to use drugs for three years afterwards. This is not correct. While Michael did continue to use drugs for three years after he stopped drinking, December 14 is the date he entered treatment and stopped using any mind-altering substances. As a leader in the recovery world, this detail is crucial to Michael’s credibility and accountability to those he serves, and Hard Prairie deeply regrets the error.

As told to Jenny Thorsen

I always had a desire for physical activity and competition. I loved pushing my body to the limit long ago when I was young. But I was always insecure, like I wasn’t good enough, like there was this block between me and everyone else. Even when I excelled at something, there was always this nagging voice in my head telling me, You’re not good enough. The people that are doing what you want to do are set apart from you. I never did figure out what exactly that stemmed from.

I fell in love with drinking and drugs in high school because they made me feel like I was no longer apart from everyone. It was a social lubricant that made me feel like I could talk to anyone, be around anyone. It started as a way to celebrate achievements. I would always drink and then once I was drunk, I wasn’t afraid to do drugs. That’s just the way it was my entire life. So there was something to do with wanting to celebrate and the only way that I really knew how to celebrate, to achieve conviviality and all that was to drink and to eventually use drugs.

The only thing is, drugs and alcohol don’t really help with physical activity. With strenuous activity, you can’t go run a hundred miler drunk or on drugs. Alcohol and drugs messed up high school sports for me. Later in life, I joined the Marine Corps and alcohol and drugs ruined that too. I would start to excel like previous times in my life, and then alcohol and drugs would take over and ruin it. In the process, I got married to an amazing woman and we had children who are now adults. But throughout my life, I still had that desire to do something big physically, but it would always be ruined by alcohol and drugs.

So there was a pattern in my life of aspiring to be a great athlete in different areas and never being able to do it, all the while stringing along a wife and children that are obviously getting neglected because I’m drinking and using drugs. My wife, my ex-wife now, left me when things got too bad, when I was using and not spending time with the children. She took the kids and moved to Vegas. I embraced her, helped load the kids into a Uhaul, and watched her drive away. And I cried. It was a painful moment, but there was also a part of me that was like, now I can drink and use drugs exactly the way I want to. That’s when I really sank into a deep and dark place in my life where I gave all of my attention to drugs and alcohol.

It was a progression over the next several years, but I went there. I drank until I couldn’t drink anymore. I started to vomit blood, and my body just couldn’t take alcohol anymore. I could no longer get intoxicated through alcohol and for six entire months, I tried with every piece in my body to get drunk, to stay drinking, and I could not. I would take the smallest sip of alcohol, the smallest shot, the smallest sip of beer, and I would puke violently. So it was over. There was one night in particular where my mother was letting me stay at her house during this period of time. I was in a room in the back of her house, I had the window open, I was vomiting blood out of the window, and I didn’t want to tell her. I was hoping that it would go away, but it didn’t. I got dizzy and fell on the floor. Then I crawled on my hands and knees to her room and told her, “I need to go to the hospital.” And that was the last time I ever drank.

My sobriety date is December 14 because I stopped drinking at that moment, but I also knew I wasn’t done checking out. I wasn’t done getting high and so when I ended up in a crack house, it’s because I devoted all of my energy to now doing drugs. That probably lasted for three years. Those three years were probably the worst years of my life. If you’ve never lived in a crack house or a drug house, it’s very chaotic. Anyone who lives there is trying to find drugs. There are times when there’s no drugs around. There’s a drought, so to speak, and so everyone’s sick. There’s never really any food or nourishment. There was a jar of peanut butter in the refrigerator that I’d take a scoop out of every morning. Someone would have to remind me to hydrate. It was very bad. I didn’t want to go anywhere. I looked horrible. I was emaciated, like a skeleton. I did not want to go out in public in any way, but obviously had to to go get my drugs. And the saddest thing in the world is when I was living in the crack house and I still had the desire to run, I would go jogging in the park and the kids that lived in the area knew me as the crack head that would run in the park. I’ll never forget that.

It took my mother and her older sister to come and rescue me and get me into treatment. It was just really, really bad, but in a way I’m glad that it got that bad because when they came to get me into treatment, I was ready. The party had been long over, and I didn’t have any energy left for the hustle of trying to acquire drugs. I felt death right around the door. When you stop eating on a regular basis, when you stop drinking water, when you never ever take care of yourself or clean yourself or change clothes for that matter for a long, long time, you just kind of feel like death is right around the corner because who lives like that, you know?

So I was going to call my aunt but didn’t know exactly what I was going to say to her. I just knew that I was in a bad spot. I thought to myself, I’ve had her pick me up and I’ve gone to her house and I’ve detoxed before. And as soon as I got better, I went right back to doing drugs. So was I going to do that again? Was I going to ask her for money for more drugs even though she’s told me she’s not giving me a red cent anymore? What was I going to do? But I knew her work number and I had no one else to call, so I was just going to dial the number and see what happened.

Somehow, I accidentally dialed Schick Shadel instead, the drug rehabilitation center. I’m in the depths of my despair and I dialed the number thinking it’s my aunt, and it’s the guy from Schick Shadel and he says, “This is Schick Shadel Drug Recovery Center, may I help you?” And I said, “Well, I don’t know, I’m a drug addict.” And he started to talk to me. He let me run my mouth for an hour about my drug addiction and how bad it had gotten. That’s when the process started. That’s when I reached out to my mother and my aunt and said, “This guy may have a bed for me in a treatment center tonight, are you guys willing to give me a ride?” And of course they’re skeptical. But I wanted to escape that house, and essentially, I wanted to escape that life.

Unfortunately, he called me back later on and told me he couldn’t get me into treatment because my insurance wasn’t going to cover it, but when I called my aunt and my mother, I got the wheels turning. So one day, my aunt left a pamphlet on the front doorstep of the house that I was living in, and it had a list of treatment centers. And the very first one on the top of the list said “Michael’s House.” I figured that must be a sign. I’m going to call them and see what they can do. That man checked my insurance and he said, “I could have you in Palm Springs tonight on a flight. And if you graduate treatment, I will pay for your flight back. But we’ve got to do this now, Michael.” And so I called my mom and asked her to pick me up.

When she came, I got high one last time. I said goodbye to that house and got in the car, but I still had reservations. I was scared. I’m thinking, oh my God, what have I gotten myself into? And so I started to curse and yell at my mother. I got in the car and I’m telling her, “The devil’s in your back seat right now. Aren’t you going to start speaking in tongues or quoting some scripture? Aren’t you going to rebuke him?” And she said, “No Michael. I’m not here to do any of that. I’m just a mother trying to save her son’s life.” And I broke. I started to cry, and the rest is history. It was December 14, 2012 - the day I stopped using drugs and the date that I entered treatment and started a life of complete abstinence from all mind-altering substances.

Michael’s House was such an oasis of recovery. I knew that I was in the right place and I knew that my life was going to change, but had it not been for some people in that facility, I don’t know if I would have made it. My first five days in that treatment center, I could not sleep. That was longer than I’ve ever stayed up on drugs. I would eventually pass out in the middle of group therapy which you can’t really do, but they would allow me to sometimes. But I remember there was a night in particular where I couldn’t go to sleep and there was a counselor that was there around 3:00 in the morning, and she was 20 years clean off methamphetamine. She said, “Michael, I just want you to go around the pool as many times as you can. Do it until you can’t walk anymore and come 6:00 in the morning when everyone has to get up, if you want to continue to walk around it, just do it.” And you know, that walk turned into a slight jog. And it went from speed walk to jog to sometimes pure sprinting, and the counselors let me run around that pool crying like a maniac. But I was letting out all the demons that I wanted my mom to rebuke. I was letting them all out, and it was all coming to an end.

There were times in treatment where when you first get there, they give you a little something to wean off of the drugs so it’s not so excruciating. But after a while, they just take you off of everything. I remember going on this hike and I’m having all the withdrawals from the opiates, and it’s just painful. And I remember being at the top of the mountain with a counselor and I said, “Man, you’re going to have to get a helicopter to come pick me up because I can’t go down that mountain.” And he says, “Trust me, we’re going to run down this mountain.” And I laughed at him because in all of that pain I was like, you think I’m running down this mountain? But don’t you know, I was running behind him down that mountain and he was yelling, “Chase me, Michael!” And I’m running down the mountain behind him. I’ll never forget that.

I got clean and sober in Palm Springs. I came home and I started to go to the 12 step meetings. In treatment, I started going on these morning walks up into the hills every single morning. Once we did that for a week, they started to take us on hikes into the hills in Palm Springs where we could see the snow, and that was a trip to me. I started to get that feeling again with physical activity. They gave us a gym membership so we could work out every day, and I started to see that I could be active again. When I got out of treatment and started going to my 12 step meetings, the counselor told me that I would find the same camaraderie there that I found in Palm Springs, so I did that. And for me and my life, they were right. The 12 step meetings are not for everyone, but they were definitely for me. I’ve been able to build a community which I feel like is family in a lot of those meetings.

However, I had a loved one who was suffering from drug addiction. They were living on the streets, and over the last several years, their physical and mental state deteriorated rapidly. It was hard for me to watch as a recovering alcoholic and addict, knowing firsthand how incomprehensibly demoralizing addiction to drugs and alcohol can be. It was unfortunate that I could do absolutely nothing for them if they didn’t want the help, but I always had hope…

I hoped that my loved one would surrender to the pain they were inflicting on themselves and others through their drug use. I hoped they would be ready to make the first step towards a new life in recovery where I could support them. So I did 30 in 30, climbing Mailbox Peak, a local mountain with over 4,000’ of gain in less than three or over five miles depending on which route you take, 30 times in 30 days.

The reason I did 30 in 30 is simply because I needed to put my energy into something else or I was going to go nuts, so I just took it out on the hill. I hiked Mailbox Peak regularly, and I would share this story with the other regulars at Mailbox Peak. I got some of my closest friends to do that hill on a regular basis and I would be with them talking about my loved one. And when you start to talk to people about your loved ones and their dilemmas, they start to open up about theirs. And that’s a thing that I never could get a grip on when I was a young man. I always thought that I was different. I always thought that my problems are because I’m different and these people, they don’t experience any of that. And that was wrong. I was so dead wrong. I went up and down that hill with judges, police officers, you name it, and so many of them seemed to have a family member that’s struggling with drugs and alcohol. So that’s when I thought of a 30 day challenge to represent the first 30 days of recovery, the first 30 days of inpatient treatment which were the most difficult but the most crucial in early recovery.

So I thought, it will emulate the experience that I had those first 30 days in treatment, doing Mailbox Peak 30 times in as many days. I’m a Mailbox maniac, but the 30 times in 30 days just sounded nuts. But I thought, I got to try this, I can do this now. I have to do something nuts.

I didn’t do them in a row. I had to do repeats to make up for days I couldn’t make it to the trail. I did two double ascents, two triple ascents, and even a five-peat in under 24 hours during this process. I spent eleven consecutive days at Mailbox Peak. From March 21 - April 11, 2022, I clocked 185.66 miles and 130,460 feet of elevation gain. Those numbers also reflect a Mailbox/Teneriffe/Si trifecta that happened somewhere in the middle of all this.

And in all that time, I thought about my loved one. I cried so many times on that mountain, so many tears. And it was nothing new really, because Mailbox Peak has been a place where I can just lay those burdens down. I can go up there alone or with a packed Saturday mountain, it doesn’t matter. Once I get to a certain elevation on that mountain and I start to open up, the tears are going to flow. It might just be gratitude. I remember not too long ago when I ran up it on the mountaineer’s route in an hour and three minutes, and there’s guys that do it in 51 minutes, but for me, that was insane and when I got to the bottom and I checked Strava and I saw that, I sat right down in the middle of the parking lot and just wept. People are walking by like, is this dude okay? I’m just sitting there crying. It was like a silent prayer. There’s a lot of silent prayers, things that I just can’t put into words to send up because it’s just, that’s the way it is now. I could get lost into the Mailbox madness and just take my mind somewhat away from my loved one, get a little bit of a reprieve. But all the while still trying to find them, still checking the places.

Over those 30 days, I had time to reflect upon my own first 30 days in recovery a decade ago. There were some distinct parallels between those days and the 30 days I spent climbing. There were certainly moments of pain and struggle followed by moments of great release, and even moments of triumph!

There’s a lot of replacement going on in a life that used to be centered around drugs, and now it’s centered around other things. I guess I notice the celebration in all things now, as corny as that may sound. And a lot of the celebration today has to do with laughter. I laugh hysterically at sometimes the wrong time, but I laugh. I tell a story sometimes in my 12 step meetings that when I used to laugh in active addiction, after the laugh, there would always be the voice in the back of my head that would say, But you’re a piece of shit, you know that, right? I don’t care who’s laughing or even if you’re laughing, let’s not forget you’re a piece of shit. That voice was always there. That voice is no longer there, and so I’m able to laugh, to truly laugh hysterically like I love to do. The celebration, it just can be found anywhere, at any given time of the day.

Just being able to know that it doesn’t take any extracurricular substance or party perks or whatever to have the celebration - I can just sit in the moment with whatever achievement, whatever breakthrough that I’m experiencing, and I can just experience it. I can feel it. And I have to have hope that this will happen for my loved one, so I will, because if I can recover, anybody can recover. I am the crack head that ran in the park!

Photo: Pete Schreiner @schreinertrailphotography

The following excerpt appears in Hard Prairie Volume 2, available now! To purchase your copy, please click the link on our homepage!

Waking from a nap, Michael shivered miserably, soggy from the moisture that had gathered in his bivy. Hardly able to control his trembling, he moved up the mountain toward Kelly’s Knob. “I just started thinking about everything,” Michael says. “One thing after another.” He thought about mistakes he’d made early in life and how far he’d come since. He thought about his parents and how it might be time to forgive his father’s transgressions. He thought about his daughter and wife, the beginning and end of all this, whatever this ended up being. And he thought about people wrestling with dark thoughts, and those who were lonely. “I cried a lot during those miles,” he says. “It was rough.”

Moving up Angel’s Rest a few days later, the temperature dropped, and rain began to fall. Michael crawled between some rocks to wait out the storm. “I should have just stayed there and slept,” he says. “If I had just stayed there and slept for two or three hours, none of this would have happened. But for some reason, in my mind, I felt I had to keep going.”

Looking at the weather tracker on his phone, Michael saw a big red blob moving his way. Not wanting to remain on the ridge, he moved down the mountain. “I was walking, getting soaked. It was maybe thirty-eight degrees. I was freezing.” Knowing he was in danger of hypothermia, Michael called his crew and arranged to meet at a shelter. Once there, however, he didn’t stay long. “There was just no way for me to get warm,” Michael says. “If I had stayed at that shelter much longer, not moving, I’d have frozen. Then they’d have had to pull me out of there. So I chose to keep running.”

Words: Chad Sullivan

Photo: Jenny Thorsen @luoyunghwa

The following excerpt appears in Hard Prairie Volume 1, available now! To purchase your copy, please click the link on our homepage!

Ask a BFC first-timer what their biggest fear is come race day and a fair share will likely namedrop Rat Jaw, the infamous mile-long stretch of saw briars. For me, it's Chimney Top, a true killer of dreams, a steep, merciless uphill march that I’d happily trade for the inconvenience of snagging briars. Last night, huddled over my map, I tapped the trail blaze with my fingers, frowning up at my husband. My race has ended here twice, I said.

He reminds me how hard I’ve worked this year and that I’m stronger. He would know: He has tolerated my before-dawn alarms and increasingly longer runs and tended tirelessly to my nutrition and routines. Once a day, every day, we talk about Frozen Head. I think about it twice as often.

They say it gets into your blood, this race, and they’re right.

For the moment, however, I’m pleasantly surprised. None of the pain I’m feeling is unexpected or unmanageable. From my pack, I eat beef jerky and a chocolate-covered Payday. When my forward mantra falters, I treat myself to a packet of applesauce, enjoying the mild, cool sweetness. Beyond my immediate needs, I try not to worry or wonder. My spirits are high.

Behind me, a pair of runners have fallen into step, their conversation breaks the silence. No, insists one of them, I’m sure of it. Marathon runners won't have to face Meth or Testicle today. Just Rat. Just the prison.

I try to imagine what that course might look like, and the reasons Lazarus Lake might have for deliberately making things easier–how silly that idea seems. But I choose not to argue, she's as certain about being right as I am that she's wrong.

We'll find out soon enough.

As the path carves its way up through the trees, her voice grows closer. Louder. How far to the next aid station? she says.

Forever, I think. Until it’s over.

Out loud, I say: I don't know.

How many minutes, then? she persists.

I shake my head. My watch is strapped to the back of my pack. I’ve long since sweat away my Sharpied list of aid stations. Neither matters. Time is a cage that exists in that world away from here. What use does the mountain have for minutes?

Behind me: "So the 50k finishers get a Croix; the marathon is dogtags. Do you get something for a DNF?"

And this time, I laugh. Gruffly. The memories, I say.

Words: Laura Presley @ltepresley

Photo: Tim Roberts @forbydigital

The following excerpt appears in Hard Prairie Volume 1, available now! To purchase your copy, please click the link on our homepage!

In June of 2022, I was a member of a film crew shooting a documentary at Western States. I spent hours at Michigan Bluff waiting for the front-runners to pass through. Of all the memorable things I saw and experienced that weekend, none held sway over me quite like Michigan Bluff, not the Escarpment or Rucky Chucky or Golden Hour. Something about the dusty, rusted-out vibe of the town felt comfortably worn-in, unbothered by the influx of out-of-towners choking off the main drag. I found shade beneath a roadside evergreen and whiled away the afternoon listening to Arcade Fire over the aid station speakers, lingering in electrified limbo, like waiting on headliners to take the stage. And when they did, man, was it awesome—how Hayden Hawks and Adam Peterman and Arlen Glick crashed headlong into town, pit-stopped with stone-cold precision, and tore on out like they each had a devil on their heels.

I’d never seen anything like it.

A few months later, in September, a fire broke out on Mosquito Ridge Road near the Oxbow Reservoir south of Foresthill. It burned for forty-six days, destroying over 75,000 acres of rough country, including portions of the Western States Trail. I watched video of the Mosquito Fire online, saw the wishbone intersection north of Michigan Bluff consumed in flames and smoke and falling embers, and sadly conceded that the town had likely been lost. Asking around in the aftermath proved fruitless. No one seemed to know what had happened to Michigan Bluff, whether it still stood or had been reduced entirely to ash.

In May of 2023, I got my answer.

Words: Chad Sullivan @ultra.sully

The following excerpt appears in Hard Prairie Volume 1, available now! To purchase your copy, please click the link on our homepage!

Words: Cory Reese

It was 2019, and I was running the Vol State 500K–a 314-mile race stretching nearly the entire length of Tennessee. Over eight grueling days, I not only threw up in that Subway parking lot, but I also dodged dozens of armadillos dead on the side of the road, slept in the lobby of a post office, got a sunburn so deep that pockets of yellow goo formed on my kneecaps, birthed blisters so large and painful that each step felt like walking on shards of glass, sewed a needle and thread through those blisters, then left the thread hanging outside my skin for the blisters to drain. I had chaffing on my legs that was so extreme that it left scars. And at mile 174, I broke down in the kind of gut-wrenching, emotional sobbing that left my shirt covered in tears and snot. I experienced the deepest depths of hell. And I think about that experience nearly every day. It was one of the most profound, life-changing experiences I’ve ever had. And there have been times since that a part of me has wanted to go back and do it all over again.

However, this year, as I followed along with the race through social media, I noticed my perspective beginning to shift. I'm so incredibly grateful for the life-changing experience I had, and everything I learned about myself as a result of it, but I have also begun to feel sad about what I put my body through. I feel sad that I willingly volunteered for such intense and extreme suffering.

And for what? To learn that I can do hard things? I already knew that. I didn't need to traverse 314 miles across Tennessee to figure that out. Was it for praise and social media kudos? I genuinely don't think so. The amount of pain and suffering I endured would never be worth any attention on Facebook. Was it ego? Pride? The need for adventure? A longing to prove my worth? Was I running away from something? Was I running toward something? I had run dozens of 100-milers before Vol State. Why was I always on the lookout for bigger, harder races? I don't know. Was it a little bit of all of those things? Again, I don't know.

I don't know.

The following excerpt appears in Hard Prairie Volume 1, available now! To purchase your copy, please click the link on our homepage!

Words: Carla Landrum

For various reasons, I pretty much stopped trail running for about seven weeks after Canyons. I still had my eye on Europe, however, and decided to enter the UTMB-CCC lottery anyway. In January 2023, I received notification that my name had been selected. I knew that I wouldn’t be able to begin training in earnest until March, and, with the race occurring in September, this left me six months to prepare for one of the hardest 100K’s in the world.

When I was 12 years old I rode Grand Prix horses, training with professional equestrian riders and breaking green horses just off the racetrack. Growing up around professional athletes, I came to understand that professional grade doesn’t come easy. It takes incredible discipline. Success is a skill, talent is the norm. I had to train harder and at a higher level than I was likely to be competing at. This is what it took to be in the ribbons, to earn money. Performance level could be intense but I acclimated well. Extremes became my climate, sweat turned into equity, grit my territory, and winning was sustenance. All of this became normal to me, in part, because of my Mom. She was an extremely good rider. She rode for sport but was good enough to be a professional. Her confidence was magnificent and she surrounded herself with people who were equally confident and capable. While tagging along with her, I trained and rode amongst some of the best in the United States. The lead-up to Canyons had rekindled a familiar level of discipline and many of my old equestrian training principles without the pressure of performing. I felt confident but knew that I needed to do more to prepare for UTMB-CCC. I needed intel. I needed to know more about what it would take to finish a race in the European Alps, so I surrounded myself with a wealth of experienced runners. Their expertise, respect for the sport, training companionship, and knowledge would prove very valuable in the end.

I signed up for a series of local trail races that I thought would best prepare me for what lay ahead. The first race was Silver States in May, a 50-mile race near Reno, Nevada, with a rather benign 9,000 feet of vert and some mildly technical trail. The race is genuine, grassroots, and old school--one of the last not gobbled up by some commercial conglomerate or franchise. The race would serve as the longest trail race in preparation for UTMB-CCC and I was knocking it out early. This may seem counterintuitive, but I wanted to get mentally comfortable with the idea of long, slow miles from the get-go. My problem was that I had about eight weeks to prepare. I ramped up religiously but slowly with both miles and climbing/descent. I mixed in a lot of swimming to keep my cardio performance up while my muscles were still developing. I forced myself to do simple strength exercises and stretches to prevent injuries to which I’m prone. The longest and hardest training run I did leading up to Silver States was not so much strategic as it was opportune. It had been a bucket list item for me to run Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim (R^3) the Grand Canyon. The climate can be so extreme that you either knock the run out in early spring or wait until fall. Spring was my window and I knew it would be good training. For safety reasons, the run ended up zig-zagging up and down the south rim twice, amounting to nearly 40 miles and 10,000 feet of climb/descent, which, for scale, amounts to only half the vert I would bag during UTMB-CCC. It was a long, slow, beautiful day of running.

Several weeks later came Silver States. My goal was to finish in 12 hours. I knew I was pushing it with a long race so early in my training. After all, my legs were still green coming off R^3. I toed the line in the back of the pack and managed to finish the race in 11 hours and 30 minutes with a fairly sore and tender IT band but no real damage.

Mission accomplished.

By Morgan Mader

Last July, having just set a new 100-mile course record at Cry Me a River, James Solomon was killing time waiting for me to finish my own race. Sitting with some friends at the aid tent, he was being casually interviewed by Runners of the Corn podcast host, Jen Heller. Banter bounced around James’ race resume and settled on his successful finish of the Potawatomi 150 earlier in the year. Jen noted that the 150’s current record holder was David Goggins, arguably one of the most recognizable figures in the sport and no stranger to testing his limits.

Without hesitation, James said :“Yeah, until I have it.”

The gauntlet had been thrown.

What followed was a year of training designed specifically to deliver on what he promised.

It takes a very specific mentality to speak with such brazenness. Goggins’ course record was over 7 hours faster than what James had run in 2022. He knew he had work to do. Added pressure mounted as the local ultrarunning community started debating whether James would ultimately accomplish it or eat his words. Runners of the Corn even went so far as to establish a wagering system in which people could donate to Goggins’ favorite charity, the Special Operations Warrior Foundation, if James broke the record. Money was now on the line.

For several months, James’ pursuit was a hot topic of discussion. Trail friends, race acquaintances, and social media all chimed in on James’ training plan. Everyone seemed to have an opinion on what it would take to get this done.

If talk is cheap and action speaks louder than words, then the lead-in to this year’s Potawatomi was all action.

James chose to race more often prior to Pot, executing an extremely successful series of timed races over the winter. In January, he set a new course record at Chill Billy, followed a month later with another course record at the Bald Unyielding Twilight Trail Trail (affectionately known as B.U.T.T.T). He often trained in freezing temperatures with eye-watering wind chills. One weekend he ran 64 miles around Lake Geneva, suffering through shin-deep snow and 25-mph winds.

And I watched him through all of this.

I was there at 2:45am when he woke for his morning run. I was there at the gym working through the push-pull sled and burpee sessions. I was there in the sauna with him 5-6 days a week for 30-minute dehydration bouts. I was there getting lapped by him as we ran hill repeats up Mt Hoy. And I was also there when we discussed race strategy, hydration and nutrition plans, and recovery techniques. We’re a team. This goal was as important to me as it was to him. I was the unwavering voice of support; the drive behind what we were going to accomplish.

Race weekend always seems eons away until it's suddenly upon you; however, we were prepared. James was in amazing shape come race day, certainly ready to make a play for the record.

I typically miss the start of James’ race as I’m out running the 50-miler. I finished just before James completed his fortieth mile. Looking to maximize my available trail time, my transition from runner to crew was nearly instantaneous. James is fully capable of handling himself, but I knew my time would come.

At the start of the weekend, the weather was some of the best that Potawatomi had ever had. It was notably hot, with temperatures in the 80’s during the afternoon, and the trail was dry and runnable. Even the creek crossings were of no consequence. Race execution was going as planned, if not better. People kept asking me about James’ pace, which was distinctly fast, and whether I believed he could maintain that for the duration. If he kept it up, he would break Goggins’ record with ease.

We had pacers lined up for the final 50 miles. James didn’t anticipate needing anyone before then. Around mile 70, he experienced his first low. With his pace being so systematic and fast, we were afforded some time to troubleshoot and focus on rehydrating. It was at this time that Daniel Williams arrived. He had finished the 200-miler the year prior and was interested in pacing. He didn’t know that he was about to be recruited to run 30 miles with James.

The night flew by as fast as the miles. After that brief low, James started to tighten his pace again, growing faster with each loop. As he transitioned from pacer to pacer, all of whom were excellent at executing what I had advised, James approached his goal with more and more drive. We were like a machine, addressing nutrition and hydration needs with precision. I would only have a few minutes with James during the transitions—only a few minutes to evaluate his mood, and what he needed, and deliver some sharp and focused words of motivation and support.

“James, you didn’t train the way you did for the last year to not get this done,” I told him. “Everything has been for this moment, these last miles.”

Saturday morning was clear and crisp, transitioning into another warm afternoon. As I tracked James’ loops, the anticipation began mounting in my chest. He wasn’t just going to break the record; he was going to break it with authority.

Watching him take off down the trail for his last loop late Saturday afternoon, I glanced down at my watch. Only 24 hours ago, I’d finished my own 50-miler. Since then, I added an additional seven miles to my step total. That’s how much running around it takes to crew a champion.

With James’ entrance song picked out for his arrival at the finish line, I grabbed a walkie-talkie and headed out to find him on the course. Race Director Mike Kelsey had asked that I radio him when James was drawing near. By now, everyone knew that the record would be broken. What wasn’t known, however, was by how much?

Sitting on a log, cheering on passing runners, I had the walkie primed and ready. Mike checked in several times, and each time I reported back a negative sighting.

“You’re killing me, Morgan.” He chuckled.

“HE’S killing ME.” I smiled and shook my head.

When I say that those 30 minutes spent sitting on that log were the tensest minutes I have ever spent doing nothing, believe me.

Then, in a blink, he was there, coming up around a tree. I let out a relieved and triumphant cheer for James and immediately reported that he’s in sight. Now on my feet, I bolted up through the trail to the open field of tents that line the course up to the finish.

“HE’S COMING! EVERYBODY GET READY, JAMES IS COMING IN!”

Moments later, James was within sight. He rang the large cowbell posted for racers finishing their last loop. Wild cheering mixed with the Metallica booming through the trees. With a warm and victorious welcome, Mike Kelsey announced, “JAMES SOLOMON! The new 150-mile record holder, a record held since 2008 by a guy named David Goggins. Welcome back JAMES!”

My body was riddled with goosebumps. I ran alongside James, pulling back just enough to allow him the finish he deserved, all the while savoring the stunning view of spectators cheering and clapping and high-fiving James as he ran past. It was a hero’s welcome and my heart warmed at the sight of it.

James finished in 31 hours and 27 minutes. He cut more than 10 hours off of his time from the previous year and smashed the course record by more than 2 hours. At that pace, he might’ve lapped Goggins.

While much of the hype and publicity was around beating David Goggins’ record, it was never really about that. Goggins is an authority on discipline, toughness, and goal-setting, all of which makes James’ victory undoubtedly richer, but, in the end, it was always just about James beating his old time. James just wanted to do better than he did before. He’s simply grateful that Goggins set the bar so high.

It's just that now, that bar is higher.

A special note is due to the individuals who donated their time and legs to pacing James during this event. We appreciate you: Daniel Williams, Lily Medina, Matt Hussung, Taggart VanEtten, and Chris Allen.

Photos provided by Ralph Deene Milam (Featured Image) and Morgan Mader.

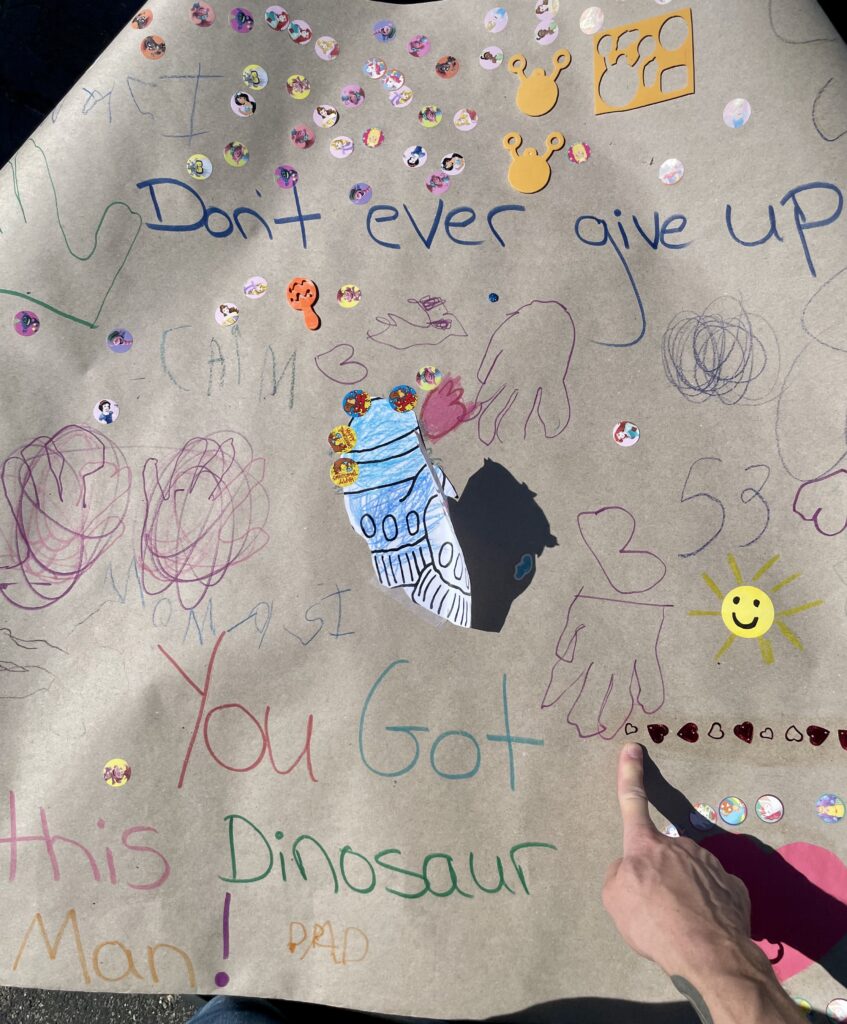

There were crudely drawn hearts and chaotic spirals and awkward lettering like a beguiling brand of cuneiform. There were shapes that looked like ghosts and a pair of paper mittens—only one of which had been colored blue—secured to the center by Thanksgiving stickers and scotch tape.

The banner read, Mom. The banner read, Dad. The banner read, alsI—my daughter’s name, which—for whatever beautifully free-spirited reason—she chose to spell backward. Our little family scrawled sweetly in crayon.

If you could have seen her face when she gave it to me—she was so proud.

Across the top, in distinctly adult handwriting, was written: Don’t ever give up. And along the bottom: You Got this Dinosaur Man! When I asked my daughter why I was Dinosaur Man, she shrugged. “I don’t know,” she said. “Because you’re crazy.”

My daughter is too young to understand distance; too young to grasp why someone would choose to run a hundred miles. She was, however, deeply aware that I was attempting something difficult, something other people seemed to think was odd or absurd, or crazy. Whoever coined the term Dinosaur Man—whether it was her, a classmate, or the teacher—it made sense to her. It gave her the ability to contextualize what she thought I was doing: Dad is doing something crazy. Dinosaurs are crazy. Dad is the Dinosaur Man.

I laid the banner flat in my tent when I set up camp. I wanted to see it between loops. I wanted it to have power and magic, and help usher me through when things grew dark. I wanted it to be the answer to past failures. All my previous DNFs were simply because I didn’t have my daughter’s swirling, chaotic, confused love in writing.

At the pre-race meeting, in the simmering grey stillness before dawn, surrounded by strangers and vaguely familiar faces, watching people double-knot their shoes and tighten the straps on their hydration packs, I thought to myself: I am Dinosaur Man.

When, during the third loop, the temperature climbed into the 80s and the humidity made molasses of the air and the sun beat down on my neck and I began to worry about dehydration, I whispered: I am Dinosaur Man.

When, in the early evening hours, lightning stabbed the earth and sky with such violence and regularity that I questioned whether I should turn back towards camp, I instead put my head down, kept moving forward, and said: I am Dinosaur Man.

When, in the hours before sunrise, rain made sloppy rivers of the trails and my rain gear failed and the temperature hovered in the low 40s, threatening hypothermia, I raged against the shitty turn of weather: I am Dinosaur Man.

And, hours later, when I rang the bell and my daughter ran out to join me on the homestretch and I sobbed as I took her small, smooth hand and we ran together toward the finish line of my first 100-miler, I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt:

I am Dinosaur Man.

Photos: Tim Roberts @forbydigital

By Morgan Mader

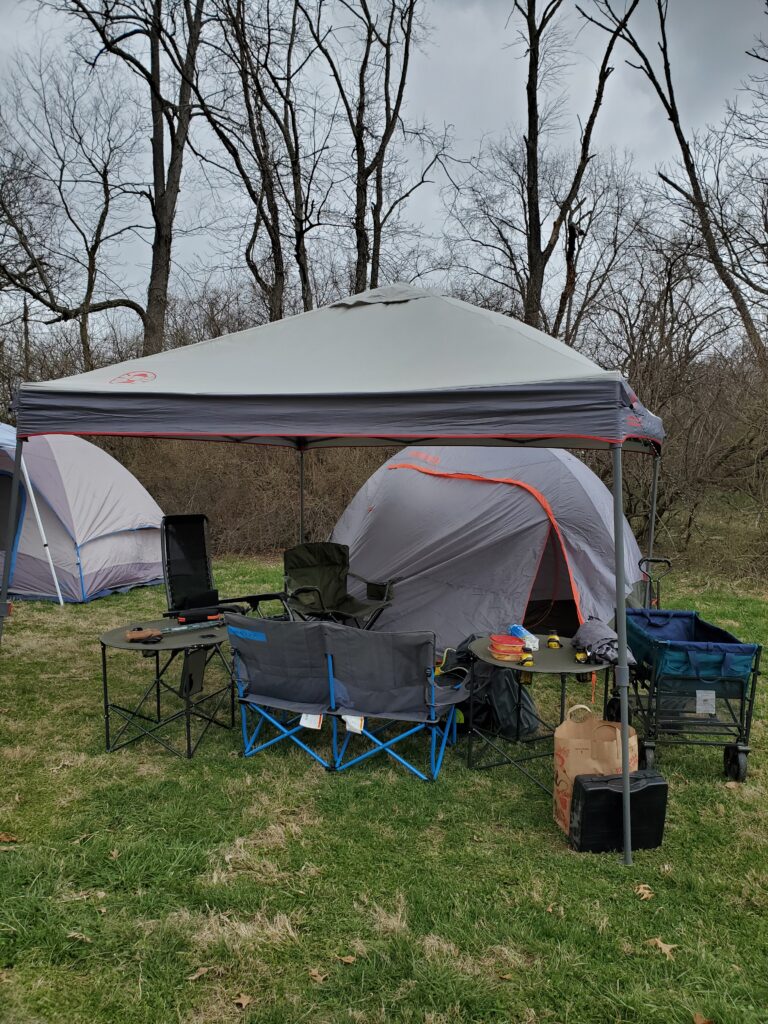

Inside the tent, it's cold and humid, but tolerable. I’m waiting on our Kelty loveseat camping chair. My pack is filled with fluids and snacks. My trekking poles are on standby next to me. I've been awake for over 33 hours—having finished my own 50-miler yesterday—and I am about to pace my husband, James, for the last 20 miles of the Potawatomi 150—honestly, a dream come true.

The Potawatomi Trail Races is an annual event held in Central Illinois, and arguably one of the most popular ultras in the state, attracting a wide variety of runners. Central Illinois, in April, is always a mixed bag of weather. One year you may experience unseasonably warm, sunny spring weather, and the next you'll be running in ankle-deep mud, soaked by either rain, snow, or hail. With a challenging, but pleasant, 10-mile loop, event distances range from 10 miles up to 200 miles.

Sitting alone, shrouded in our oversized camping blankets, I flashback to two years ago. It took a lot of convincing to get James to concede to tackling only the 100-miler for our first visit to Potawatomi. As fate would have it, the race was canceled that year (not an uncommon occurrence in 2020) and everyone who had registered were offered free race distance upgrades for 2021. That was all it took for James to go all in for the 200 miles.

In 2020 we were just starting our second season of ultra-races. We barely knew how to run 100 miles. Now we expected to double that distance. In the end, neither James nor I were prepared to tackle the complications that come with executing a 200-mile race, and James pulled the plug 100 miles in.

Back in the tent, I laugh to myself as I ruminate on how James split the difference for this year’s race, committing to the 150-miler. A couple of years ago, he won Illinois's Temptation 200 (which, in reality, clocks in closer to 124 miles). What're another 26 miles on top of that?

Ten hours ago, James rolled into camp at mile 90. Having long since finished my 50-miler, I had transitioned to crew. I filled his bottles and pulled out his nutrition for the upcoming loop.

"Morgan, I need you to get me pacers."

I cocked my head to the side, slightly taken aback. James never requested pacers.

"Do you want them for the last 5 loops?"

We were walking away from the tent at this point, mostly on autopilot, picking up speed as we approach the trail beyond.

"Yes. Make it happen."

And off he went. I had 2 hours to come up with pacers and a plan.

Potawatomi is a prime example of how folks in the local ultrarunning scene view racing and community. While my task seemed tall, I knew that James was well-liked within the community and people would likely show up for him.

One question James and I are often asked is, “How do you prepare for these distances?” I often wonder what they’re looking for—what kind of answer they’re hoping to get—a simple response with a simple solution or some kind of elixir for success? This was James’ first attempt at a distance greater than 124 miles. His solution was to run a 500+ mile month in March. He and I have gone back and forth on whether he was overtrained for the 150-mile race in 2022. By standard definition, overtraining traditionally encompasses both a physical and mental state of being. James was emotionally ready to take on the 150. He felt fresh and energized for the experience. But we’ll never know whether his leg fatigue and niggles during the race were due to the heavy training or were simply a result of running 150 miles of trail over a cold spring weekend. Only future attempts will reveal the answer to this question.

With James’ pacer request at the forefront of my mind, I immediately darted over to the tent area, where our friends, the Goodmansons, had set up camp. I knew without a shadow of a doubt that they would be able to point me in the direction of some willing, on-the-spot pacers. As luck would have it, one of James’ good friends was sitting there and instantly volunteered for a loop. He also volunteered another pacer, so James was set for miles 100-130.

However, it was going to be up to me to pace him the last 20 miles.

Now, to some, that may sound like a piece of cake (and don’t get me wrong, I love cake!). The way we in the community often talk about distance, it makes sense that someone outside the community might think that twenty or thirty miles is nothing to us.

That’s not always true, though, especially when you’re talking about trail racing.

Ever since the start of our ultrarunning careers, I’d had a deep desire to pace James. Once it became clear that he was an exceptionally strong runner who could hold a solid pace well into 80-100 miles, I’d assumed this was most likely a pipe dream. Yet now was my chance to see if I had what it took to run with him and provide the ultimate form of support in the process. This would be no small feat. I had already run a very successful 50-mile race and essentially paced a friend of ours through every step of his first 50-mile finish. Since then, I had transitioned to crew, sleeping very little in the meantime. Additionally, by the time James would be ready for his final 20 miles, it’d be nighttime, which is traditionally the most challenging time to run. It’s dark. It’s cold. By then I’d have been awake for who knows how many hours and James would be going on more than 35 hours of non-stop running. This was a BIG deal.

Never one to take anything lightly, I was looking forward to the challenge. I would finally get to see firsthand how James handled extreme distances. Usually, I get a quick kiss and a wave as he laps me on a looped course, but now I’d get a sense of what he was thinking and how he responded to adversity. This was going to be 20 miles of grit, run in the middle of the night—not something we were unfamiliar with, as it’s often part of our training routine. There was something natural and serendipitous about us wrapping up this race together, alone in the woods, most likely as the sun was coming up.

If that isn’t romantic, I don’t know what is.

When James finishes his tenth loop, I’ve got his first pacer ready to go, which energizes him. He purposefully moves through our campsite, switching out handhelds that I’ve topped off with Fluid, his preferred electrolyte supplement. James stuffs some Spring nutrition down the hatch and then he’s off, his friend in tow.

With him gone again, I slowly start getting ready for my pacing run. The weather has warmed up, and the sun is out. I begin to go through my thorough pre-race routine. First, it’s the Normatecks. We invested in both the hip and leg attachments which have been extremely valuable in promoting leg recovery. If you train as much as we do, it’s a great investment. I lay on our zero-gravity chair going through each session—first the hips, then the legs. I cover myself with a blanket, because it may attract attention, but this is also an opportunity for me to relax, read, and even take a short nap. Once wrapped up, I start prepping my pack, hydration bladder, portable nutrition, trekking poles, headlamps, and running gear.

When James arrives at camp again, he takes a bit more time at our tent. Still, he is efficient and focused. It’s nothing but love and support, then he’s off again, this time with a different friend.

James is hungry this year, it’s obvious.

Last year’s DNF of the 200-miler taught us some valuable lessons. Races don’t work linearly. Planning and executing a 100-mile race is one thing, attempting to double that is something else entirely. The challenges and pain are increased exponentially. Being able to navigate things like poor weather, foot and gut health, and gear complications, all while maintaining a positive headspace, is absolutely essential. Admittedly, I was not prepared to support James for the 200-miler in 2021. Could I have fumbled my way through it? Of course. But it would take crewing James’ 150-miler in 2022 for me to learn what it meant to be truly excellent crew.

It’s late afternoon, transitioning to early evening. I’m keeping track of James’ average loop times and know when to expect him. He has one more loop before I’m on deck. I see James coming out of the woods into the clearing, following the long single-track trail that runs toward the start/finish area.

For as long as I’ve known James to run, his gait has been imprinted in my brain. I could recognize him running in the dark from a quarter mile away. I know when he looks fresh as a spring daisy, and I know when he may be experiencing some niggles.

As he emerges from the woods, I can see the miles working away on his body. He’s run 120 miles, and he’s sleep deprived. James trots into our campsite saying he is cold. I immediately fly into action, grabbing his jacket and bundling him into two oversized blankets. Suddenly, James does something unexpected. He pulls the blankets up over his head, becoming fully encompassed within them. As I watch, I hear a soft, almost inaudible, choking sound—James is holding back tears. I crouch under the blankets with him. He’s quiet now. I slowly rub his back. I know that just these brief few minutes of comfort can be enough to relieve his pain and get him focused again.

To mitigate his cooling down, we decide that James will leave camp with a down jacket that he’ll wear for the first mile. At that point, the trail loops back around near the starting area and I’ll be able to pick the jacket up from him after he’s warmed up.

“Okay, James, it’s time to get back out there. You’ve got one more loop, and then I’m going out with you for the last two.”

He comes out from under the blankets and stands. A small army of people has gathered to assist James with whatever he needs. They too are now invested in his finish. This is the community I’m talking about—people coming together to help each other achieve unbelievable feats of human prowess.

James and I move towards the starting line, left alone to enjoy a brief personal moment. He looks at me as we’re walking: “Morgan, I’m just so tired. I’m so tired.”

My heart cracks slightly. This is one of the hardest parts of ultrarunning. I know James is looking at me—right now, at this moment, having run 120 miles—and is begging me to let him sleep. I also know—right now, at this moment—that he’s also begging me not to let him sleep. He’s begging me to keep pushing him forward. When you love someone, you are all too familiar with the desire to prevent them from experiencing pain. That part of me wanted to make it stop, to give him some rest. But I know James. My role, then and there, was to be the solid, unwavering beacon of light ushering him forward toward his ultimate goal of finishing the race. There would be no stopping. There would be no sleep.

“I know you are, but you have to keep going. You can keep going. Just one more loop and we’ll finish this together.”

The down jacket is on him. He’s holding a warm cheese quesadilla. James looks at me, turns to look down the trail, then looks back at me. I kiss him on the mouth, then on the cheek and whisper, “Go get it.”

As he turns to trot down the trail, pacer by his side, my heart, which had been on the verge, fully breaks. The tears come quietly. I can’t let him see me. I chastise myself for crying but recognize that it’s healthy to let it out. For the final 20 miles, I would have to be tough as steel.

It’s dark now, after 10 pm. I’m sitting quietly in our tent; my pre-race ritual complete. I threw in a Theragun session and applied Amp to my legs—doing what I could to make this feel like an entirely new run. A full day removed from my race, I feel like it almost never happened. But that could just be nerves. I’m wired, but laser focused.

Suddenly I hear a familiar voice outside the tent.

“Hey Morgan, Jeff says that James should take a nap before he heads out for the next loop.”

Our friends, the Goodmansons, are relaying me a message. Jeff has seen James on the trail and feels like he needs sleep. I listen, then pop my head outside the tent to consult with a friend who is also crewing for James. I’m always open to receiving feedback, but this suggestion gives me pause. How do I best address it while keeping an eye on the end goal? No one knows James better than I do. I can’t let that slip my mind, especially at this crucial turning point. We decide to split up. He will go towards the trail opening and intercept James, then report back to me James’ own opinion as to whether he should continue.

I don’t have long to wait. I’m back in the tent, trying to stay as warm as possible, the temps have dropped back into the 30s again. All is quiet outside. Then, like a boom from across the woods, I hear, “MORGAN, HE'S NOT STOPPING!”

Immediately I get goosebumps (and still do thinking about it today). The sheer grit and determination it takes to reject the offer to stop and rest is astounding. I’m up. My pack is on. Trekking poles are in my hands. Headlamp is on. The tent is set for a quick transition when we return for our final loop.

James moves past our tent. I’ve bagged up hot food for the trail. He’s being attended to by a slew of friends. I lose track of time—unaware of how long the transition takes—and then we’re off down the trail together.

Once we make it down the first long descent, the trail evens out into prairie. It’s a classic Illinois race. My goal is to be encouraging and upbeat and keep him moving. I start in front. It’s painfully evident that James is tired. I encourage him to run for 10 steps, then we walk. I encourage him to run for 15 steps, then we walk. It goes like this for a while. I would be lying if I didn’t admit that much of this was a blur. It’s pitch black beyond our headlamps. With sleep deprivation, the scenery appears strange. You can recognize landmarks and turn them into benchmarks throughout the loop. James entertains this for a while, explaining to me what our next benchmark is as we move through the loop. We move through creek crossings—the water up to our knees—down narrow single track, up steep ascents that offer a rope to assist the climb. James’ ability to run downhill has been whittled away. He can still run and climb, but it’s clear the downhills are painful. I continue vocalizing positive thoughts, but after a while, James is not interested in conversation. It also becomes clear that he prefers me behind him, not leading. This is fine with me. It’s not my race and I’ve never paced him before.

Having brought my phone with me, I call our friend who is waiting at the tent. I update him and tell him which food items he should have ready to go. This has turned into a seriously coordinated event, and it’s exhilarating.

The end of the loop arrives sooner than I anticipated, and my legs feel great. This is astonishing to me, and I’m grateful that they’ve held up.

James has 10 miles left. He’s about 2.5 hours ahead of the next competitor. This race is his for the taking, but we have to keep moving. At the start/finish tent, he’s standing, eating a cheese quesadilla. Four people are fixing him up with a winter hat, food, and fresh bottles. His eyes are closed and I’m convinced he’s fallen asleep standing up. When we take off again, James is disorganized on the trail, almost as if he were drunk. It occurs to me that he never really needed anyone to pace him. I am strictly here to make sure he is safe.

Eventually, James steadies himself a bit. This far into the race, muscles and neurons aren’t firing as they should be. A clumsiness is more apparent in his movements. About two miles in, James’ headlamp is dimming. This is concerning but not an outright issue. I plan on changing his batteries at the next clearing. It’s ghastly quiet—the only sound is our shuffling steps on the woodland debris strewn over the path. It’s cold and still. I catch myself focusing heavily on my feet, aware of the roots and leaves we’re moving through.

Without warning, James falls.

He flies forward, owning the fall Superman-style. His trekking poles shoot off—one to the right, one to the left. We’re in a clearing, approaching where the Totem Pole aid station used to be. Now the area is turning into a soft grass field. There’s not much here to trip on, but James found what appears to be the smallest of twigs and it completely obliterates his balance. He goes down. I’m standing behind him analyzing for injuries. He rolls over on his back, and it’s clear he isn’t injured—a total relief.

James lies on the grass staring up at the clear, spring night sky. It’s completely silent. I’m not even breathing. I look into James’ eyes. They’re wet and shiny, reflecting the moonlight. I can’t ignore the thought that he is about to cry. If he does, it will just about shatter my heart. Without thinking, I bend over him and firmly say, “Get up. Get up, James.” His eyes shift to look at me—registering my presence for the first time since he hit the ground—and they are suddenly clear. I see a distinct shift occur, almost a click. My hand shoots out. He grabs my hand, and we use our collective strength to get him to his feet. James stands there. We’re eye to eye now. I encourage him to take a moment to organize himself. I give him my headlamp and take his dimming one.

No additional words are spoken. James reorientates himself and starts up again, only now his pace has quickened. We keep our trekking poles up as we run through the darkness. It’s after 3:00 am now, the witching hour. We continue along the trail, James taking fewer walking breaks.

At Heaven’s Gate—an exceptionally runnable mile-long loop—my legs start to ache. I curse this for happening now. Not wanting to ask him to slow down, I talk myself through the pain. It’s my turn now to see what I’m truly made of. I don’t want him to have to drop me.

I will not miss him finishing. I will push through my fatigue. I will be there for him.

I am not exaggerating when I tell you that James’ lead-up to finish is the most unbelievable thing I’ve ever seen. James was a man possessed. He ran the last 8 miles. We didn’t speak a word. We used our poles on the descents, but when it was time to run, I’d watch them choke up in his hands, and I’d mimic him, knowing we were about to take off. We were like a well-oiled machine. I’ve never felt more connected with another human being than during these last 2 loops. There was only one goal. One. It didn’t take words; it didn’t take daylight. It only required our minds to be cosmically interlinked in this one unified pursuit. Never have I run an easier 20 miles.

As we approach the final uphill, anticipation is vibrating between us. James bolts up the hill and I use everything I have left to keep up. As we trot around the final bit of wooded trail, we pass the cowbell, and I ring it with the extreme might of what an army would use to announce the presence of the enemy.

It’s 5:30 am. I don’t care. I want to wake everyone up.

“JAMES SOLOMON, 150-MILE FINISHER COMING THROUGH!” I boom across the campsite.

Cheers erupt from the darkness, the finish line lit up like a beacon of salvation. We fly to the finish, towards a celebratory and triumphant reception.

James is immediately met by the Race Director, who hands him his awards for first place. Finishing in 41 hours, James hasn’t broken the course record. Still, he ran hard enough to bring us home a victory. Friends, aid station volunteers, and spectators crowd around us for hugs and photos. I look at James. It’s the first time I’ve seen his face since he’d fallen. His eyes are alert, his smile infectious. He doesn’t look like he’s just run 150 miles, without sleep, in the woods, in the cold. And it occurs to me that James might have more in him—that he could have pushed himself even further. I see it now with my own eyes—clear evidence that we’ve only just scratched the surface of his potential.

Photos provided by Morgan Mader

By Shan Riggs

I was looking for something to read in the airport bookstore when I came across Dean Karnaze's book, Ultramarathon Man. In the book, Dean talks about running now-famous races like the 135-mile Badwater Ultramarathon and the 100-mile Western States Endurance Run. He also tells stories about unheard-of feats of endurance such as running a 200-mile relay race solo and 350 miles in one go.

I was intrigued. Despite having gone four days of practically no sleep, I read throughout the entire flight and finished the book as soon as I got home. The next day I signed up for my first ultramarathon, the Chicago Lake Front 50-Mile.

At the time I had mostly run for fitness and had only one marathon under my belt in which I felt as if I might die and still barely finished in under 4 hours. I thought that one marathon would be my last. But after the Chicago Lake Front 50-mile, I caught the ultra bug. I also realized that I was actually competitive at these crazy things. I have now completed over fifty ultramarathons and have been fortunate to win some along the way.

Beyond competing in races, I was intrigued by the idea of someone pushing themselves to their limits as a form of self-inspection. How far can I push myself when every cell in my body is screaming for me to stop? I’d already completed a handful of 100-milers, the longest races I could find - how could I push myself even more?

In early 2008, I hit upon an idea, what about a 200-mile run? Would I be capable of something like that? I was living in Chicago and volunteering for a nascent non-profit, Meddles 4 Mettle. Started by Dr. Steven Isenberg of Indianapolis, the organization takes in medals donated by endurance athletes and awards them to courageous kids who are under treatment for a serious illness such as cancer.

At the time, the organization was active only in Indiana and Chicago and they wanted to get the word out to encourage more donors and volunteers. Turns out it was about 200 miles from Indiana to Chicago; interesting. What if I ran non-stop from my home in Chicago to a hospital in Indianapolis as a way to raise awareness (and money) for M4M? This could be the perfect physical test for a great cause. The "Medals 4 Mettle, Windy 2 Indy" run was born. Starting on a Saturday in June 2008 I left my home in the South Loop of Chicago and Monday morning (50+ hours later!) I arrived at the Clarion North hospital in Indianapolis. It was the most difficult two days of my life. Previously, I had done races in which I needed to run overnight without sleep, but this run required two nights of sleep deprivation. I actually fell asleep several times while running and nearly fell into a ditch. With only 45 minutes of sleep, I made it to the finish on Monday morning greeted by reporters, family, and friends. Many other fun things happened on that run, if you are interested you can read about them here.

In addition to proving to myself it could be done, my support crew and I raised money and brought a lot of visibility to M4M. I did many interviews with radio, tv, and print outlets, which gave me the opportunity to talk about M4M and its mission. M4M now has over 70 chapters around the world. While I can't claim this run helped them grow from two to 70 chapters, it did get the ball rolling. It also proved a concept. These unique endurance challenges don’t just give me a way to test my limits, but they can also direct more support and awareness to charities.

A few years later, after recovering from M4M, and running many more ultramarathons, I started talking to friends about other long-distance challenges. That’s when someone asked if anyone had ever run the length of Illinois. We looked into it and it turns out no one else had been crazy enough to try. In July 2013, a small group of us decided we would give it a shot. 410 miles in one week, 50-75 miles a day, about 60 on average - all to support some local running-related charities.

It was a challenging week, to say the least. It involved blood and pain in feet and other places, hyperthermia on a summer's night, pushing a broken down truck, flooded roads and other near calamities. But in the end, I and one other person, Chuck Shultz, completed the run.

Since we had run literally all of Illinois, it was time to look at places farther away from home. So in 2015, another small group of us ran 166 miles across Panama in order to raise money and awareness for a local school. It was a memorable adventure. It felt like the entire country had our backs. There was a lot of media coverage, with hundreds of people running with us, riding their bikes, or driving their cars during the last several miles. We even had a fireworks display at the finish.

Fast forward to 2020, I was living in Connecticut and working for the Hartford Marathon Foundation. When March 2020 happened my work was suddenly on hold and I had extra time on my hands. This is when I decided to do something that I had dreamed about doing for a while; run the United States from coast to coast. It ended up being a three-month, 3,255-mile trip, running about 40 miles per day. The run received a lot of local and national press and raised over $45,000 for Foodshare, part of Feeding America. It also produced a new brand and website: Shan Runs Across America. You can see a short video about that run produced by Connecticut Public Media here. After seeing what I could accomplish, I was more committed than ever to this expedition-style run for charity.

In part because of the Shan Runs Across America run, the next year I was invited to be a member of Team USA in the inaugural 1,000-mile relay race across Australia called 1,000 Miles to Light. The concept was Team USA vs. Team Australia, 4-person teams with each runner doing 5-kilometer legs across New South Wales, organized by world-famous ultrarunner Pat Foster. The run supported Reach Out, an organization that supports youth mental health, something very timely and needed in 2021. Also, it turned out that another member of Team USA happened to be the guy who inspired me to get into all these crazy runs in the first place. The Ultramarathon Man himself, Dean Karnazes. Dean and I had run into each other a few times over the years, but this was the first time I had the chance to explain how much of an inspiration he had been to me.

Like most things in 2021, Covid changed our plans. Because of new restrictions after we landed in Australia, we moved the event to a bubble at an Army base, rather than running across all of New South Wales. Still, we had a ton of fun. We got to run with Kangaroos, I almost got eaten by a dog, we raised some money for Reach Out and there was a very cool full-length documentary made about the whole expedition (they are still looking for U.S. distribution). Dean wrote a great write-up about the run in an article in Ultrarunning Magazine.

That brings us to 2022 and the most epic and meaningful trip to date, the East Coast Greenway Expedition. My partner, Joshuaine (Josh) Grant, wondered aloud one day if anyone had run the entire East Coast Greenway, a 3,000-mile trail that runs from Key West to Canada through twelve states and 450 communities. It looked like there had been some bikers and a few walkers, but no runners had completed the entire route. So we reached out to the small non-profit that supports the greenway, the East Coast Greenway Alliance, to work together to promote the greenway and support the alliance's mission. We planned to bring attention to the Alliance with a run/bike expedition where I would run 40 miles a day while Josh rode her bike, towing our gear (while working full time). By the time we finished 78 days later, we had raised around $20,000, been in 50+ news articles, and met with hundreds of friends and supporters. Oh yeah, we also got engaged! Mary-Paige McLaurin of the East Coast Greenway Alliance put together a wonderful short film on the expedition here.

So, what now? Well, obviously the next expedition is a 2000-mile run/ride from Canada to Mexico on the west coast! We are working with the Adventure Cycling Association to support its mission of inspiration and adventure. We plan to start in September of 2023. You can find more information on our website, where you can find links to our Instagram, Facebook and Strava.

On to the next adventure!

Photo: Mary-Paige McLaurin @mpmclaurin

@eastcoastgreenway